Until everyone gets their own Kingdom

About: Eric Andersen

By: Per Brunskog

By: Per Brunskog

He didn't pee on the Red Square in Moscow on the day Nikita Chrusjtjov was forced from power. However, he created a miracle outside the Royal Palace in Copenhagen and moved London from England to Bad Salzdetfurth in Germany.

Opus: 18

“We'd might as well call it Opus 18, I don't entitle my projects something other than Opus followed by a number” Eric Andersen answers when I ask about the title of one of his works. The numbers doesn't follow any system, so it's impossible to interpret the work based on the title or even list his work chronologically by their names.

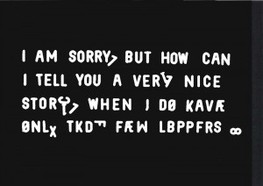

Opus 18 is a photography of a text. The text attempts to say: I am sorry, but how can I tell you a very nice story, when I only have these few letters. The story behind this work is that he found a tiny box with letters, the type of letters used when making titles for small-film. There weren't many letters in the box, so he was forced to use the wrong ones, twist and turn them so they would look like others. Still we understand the text. Or, what is there really to understand? It is a play with symbols and their significations. A play that contains fascination.

The photo, titled Opus 18, was part of the retrospective exhibition “Liaison” by Andersen at the gallery Kunsthal Nikolaj in Copenhagen last spring. Andersen himself calls the whole exhibition an installation based on the visitors' movements, or “procession” through the structure. The retrospective material from his 52 years in the arts was disposed “so that visitors would have something to rest their eyes on” as they were slowly moving strolled through in the installation. The installation is a scaffolding over four levels, rising from floor level to the height ceiling in the previous church hall. Or as he describes the work, “a cathedral built inside a church”. Every third day the exhibition ended with Eric making a 15 minute long improvised concert on the organ that is still left from the time when the building was used as a church. On this day he also added or removed something from the installation. Every Thursday the audience was invited to a jam session, which took place in the scaffolding. Liaison is not accompanied by a catalogue or even an exhibition text, but offers a wheelbarrow filled with dictionaries. This is not done to mystify the artworks, it simply makes a statement about Eric Andersen's position against traditional art mediation where the audience is served a specific interpretation. On the contrary, his work is highly transparent and he is more than happy to talk about his own fascination towards it. A small side track can develop into a long story, as in Opus 18, displaying how little we actually convey using our language and therefore we end up writing something that is so filled with mistakes, still our brains add up, make meaning and create structures, where there is no inherent meaning or structure. Andersen included the wheelbarrow because several visitors expressed curiosity about the meaning of the words used in the exhibition, it is there so that the visitors can further spin upon their own curiosity. According to Andersen this is how art mediation should function “Art should be mediated so that the viewer can immerse into the work and point out aspects that are not obvious, not to explain the artwork.”

What Andersen finds interesting is the experience of art, not the interpretation of it. This is why he wants to replace the Aesthetics with an Aesthesy. Aesthetics is about hierarchical coding, a sorted system. Aesthesy, however, is an overall attention towards the artwork without interpretation. The Aesthetics aim to close the artwork. The Aesthesy wants to stay within the experience, the state we are in prior to having formed a firm perception. A few days after my interview with Eric, I found that he already had given a different piece the title Opus 18, and the photograph I described above the title Opus 20. This, which only has significance for art historians and others who aim to give a rational 'true' description of the world, would create some sort of confusion. A stick in their wheel which must please Eric Andersen for sure.

“We'd might as well call it Opus 18, I don't entitle my projects something other than Opus followed by a number” Eric Andersen answers when I ask about the title of one of his works. The numbers doesn't follow any system, so it's impossible to interpret the work based on the title or even list his work chronologically by their names.

Opus 18 is a photography of a text. The text attempts to say: I am sorry, but how can I tell you a very nice story, when I only have these few letters. The story behind this work is that he found a tiny box with letters, the type of letters used when making titles for small-film. There weren't many letters in the box, so he was forced to use the wrong ones, twist and turn them so they would look like others. Still we understand the text. Or, what is there really to understand? It is a play with symbols and their significations. A play that contains fascination.

The photo, titled Opus 18, was part of the retrospective exhibition “Liaison” by Andersen at the gallery Kunsthal Nikolaj in Copenhagen last spring. Andersen himself calls the whole exhibition an installation based on the visitors' movements, or “procession” through the structure. The retrospective material from his 52 years in the arts was disposed “so that visitors would have something to rest their eyes on” as they were slowly moving strolled through in the installation. The installation is a scaffolding over four levels, rising from floor level to the height ceiling in the previous church hall. Or as he describes the work, “a cathedral built inside a church”. Every third day the exhibition ended with Eric making a 15 minute long improvised concert on the organ that is still left from the time when the building was used as a church. On this day he also added or removed something from the installation. Every Thursday the audience was invited to a jam session, which took place in the scaffolding. Liaison is not accompanied by a catalogue or even an exhibition text, but offers a wheelbarrow filled with dictionaries. This is not done to mystify the artworks, it simply makes a statement about Eric Andersen's position against traditional art mediation where the audience is served a specific interpretation. On the contrary, his work is highly transparent and he is more than happy to talk about his own fascination towards it. A small side track can develop into a long story, as in Opus 18, displaying how little we actually convey using our language and therefore we end up writing something that is so filled with mistakes, still our brains add up, make meaning and create structures, where there is no inherent meaning or structure. Andersen included the wheelbarrow because several visitors expressed curiosity about the meaning of the words used in the exhibition, it is there so that the visitors can further spin upon their own curiosity. According to Andersen this is how art mediation should function “Art should be mediated so that the viewer can immerse into the work and point out aspects that are not obvious, not to explain the artwork.”

What Andersen finds interesting is the experience of art, not the interpretation of it. This is why he wants to replace the Aesthetics with an Aesthesy. Aesthetics is about hierarchical coding, a sorted system. Aesthesy, however, is an overall attention towards the artwork without interpretation. The Aesthetics aim to close the artwork. The Aesthesy wants to stay within the experience, the state we are in prior to having formed a firm perception. A few days after my interview with Eric, I found that he already had given a different piece the title Opus 18, and the photograph I described above the title Opus 20. This, which only has significance for art historians and others who aim to give a rational 'true' description of the world, would create some sort of confusion. A stick in their wheel which must please Eric Andersen for sure.

Persona non grata within the Danish art

All sources I have found about Eric Andersen, state a variety of birth dates and birthplaces. With a happy grin he also tells how he when coming up to his 70 years anniversary sent a biography to a Danish newspaper that was completely wrong. None of the editors discovered the errors, he points out with a pleased laughter.

Exactly as happy as he looked when he talked about his biography scam, he also looks when he describes his relationship with the Danish art scene, a world of which he never has been completely embraced, “I am a persona non grata within the Danish art scene”.

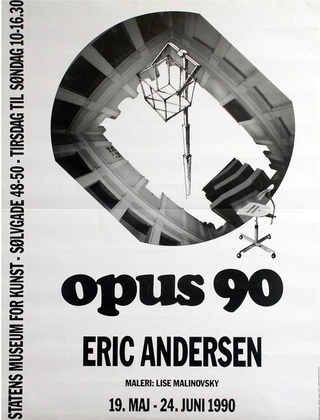

He tells me that our friend in common Jes Brinch, who is the one who made this interview possible, is one of few artists he associates himself with. This, a result of having over many years eluded and revealed abuses of power both within the hierarchical structures of The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and the very influential Carlsberg Foundation. The most well known feud – the conflict about “The hidden painting” – went on against the National Gallery of Denmark in the 90ies. The feud originates in a giant installation by Andersen at the National Gallery entitled Opus 90. As part of the installation he had his colleague Lise Malinovsky paint a painting directly onto one of the gallery's walls. As soon as Malinovsky had completed the artwork it was covered, repainting the wall in white. After the exhibition the painting was bequeathed to the National Gallery with the precaution that the painting should remain there for eternity, to never be archived or removed.

A few years later a large extension of the Gallery was initiated, with intentions to demolish the The hidden painting wall. Andersen hired a lawyer to protect his artwork and a giganticjuridical- and medial process rolled on. That this conflict is now definitely over, is confirmed by the full story being described in the Gallery Journal, SMK #6, 2013, where Andersen is interviewed. In the article the artist contently states that now the artwork is considered “a pearl....a main piece in the Gallery's collection”. The process itself, Eric explains, ended with the resignation of the then superintendent. Also, a compromise was reached, agreeing that the wall could be de-attached to the building and moved to the entrance hall where the art piece now resides.

Avant-garde

In Eric Andersen's body of work one finds a care for, and playing with, contradictions. A scepticism towards the stripped worldview of rationality. Andersen does not attack the common knowledge within but shows that there is so much more that constitutes the truth as well, and he stirs up what the rest of us strip away to make the world rational and apprehensible. A constant rebellion against norms, consensus and authorities that limit freedom. And maybe it is specifically due to his care for freedom of power of thought that he has never been properly included in the Scandinavian art scene. “The hidden painting” is one of very few pieces, representing his body of work, which has been included in the larger Scandinavian art collections.

When doing my interview with Erik Andersen I note that he regards both Fluxus and his own work as avant-garde. Something that no artist of the later generations would do, as it resonates the notion of an artist as a genius. An understanding just Fluxus and Andersen themselves agitated against. Also, avant-garde is a term that perpetuates hierarchical evaluation and thereby states that it is a good thing considering an art historical perspective of someone being ahead of their time. In his later communications he explains:

“Neither I nor the others that were part of introducing Inter Media Art during the years 1958-1962 wanted to view ourselves as avant-garde or believed that we were avant garde. The term is only used because in hindsight it shows that we created an understanding of art that completely challenged the definition of art. Everybody has to acknowledge that during the last fifty years the arts have gone through a large revolution”.

Today, not many recognise the term, Intermedia Art, not because the art form is distinct, but rather it has become so common that artists choose to show their matter in different contexts, shift between their media and jump between genres like music, literature, painting, theatre, film and so on, that this doesn't surprise anymore. Semi-incorporated in the term Inter Media Art is also the notion that an artwork does not necessarily have a firmly defined beginning or end. The artwork is not locked to its object or its event, even though this is rather uncontroversial today.

Not only during these years around the 1960s did Eric appear as ahead of his time. There are numerous examples, Opus 90 being one of the more obvious ones. Today, 23 years after it's erection it is striking how it resembles the art that appeared five – even fifteen years later. The art that belongs to the heydays of relational aesthetics, when the audience as participants not mere passive observers became the trend even within the wider world of art. However, Andersen's approach differ from the relational art in that he doesn't convey an explicit message through his construction of relations. Where Andersen creates experiences, the relational artists creates meaning through establishing interpersonal relations or micro utopias.

Opus 90 consists of three parts: from the ceiling hang cubic meter large cubes or boxes in different colours which visitors could crawl into to sit. In each box you would find objects put there by the artist: books, a meal, today's newspaper, Soviet theatrical makeup, real gold bars, a walkie-talkie to eavesdrop on the museum guards or to call in a fake alarm. To access the boxes, some hanging 15 meters above the floor, you would have to ask the museum staff to transport you to your chosen boxusing a sky-lift. However, you were not free to choose any box, you had to choose one in the colour that the artist decided was the colour of the day. On the floor, a hundred spinning chairs labelled whit the text: Become a member of Eric Andersen's random audience. These chairs were painted in the same seven colours used on the boxes, and the audience was free to move them around changing their location throughout the museum. The third part of the art piece was the The hidden painting, described above.

It is obvious when Eric talks about Opus 90 that he regards it as one of his most important works. He explains that the court process of “The hidden painting” as with all the turmoil he made in the Danish art scene was merely for himself to enjoy, though his eyes shine with pride when he tells about how he jested the obsolete structures of the Royal Danish Academy and how power greedy people fell in the process.

Fluxus

The Kunsthal Nikolaj in Copenhagen, previously called Nikolaj Church was also the venue where Eric Andersen's artistic career took off for real. This when he nineteen years old participating in one of the first Fluxus arrangements. Exhibitions that today are recognised as legendary and probably one of the few instances where Scandinavians put their profound mark on the international art scene. The writings about the Fluxus movement can fill meter upon meter of shelf space, however, the more you read the more confused you get. On the contrary, Eric's version is simple and comprehensible, “It was never an -ism, it was simply a network of artists with the one thing in common that we were involved in Intermedia Art early on (...) The Network meant having somewhere to stay when putting on an event somewhere in the world, and it made collaborations available.” Then Eric points out that he himself, as with most other Fluxus artists, has done more work outside of the Network than within.

The Fluxus movement's self-appointed leader was George Maciunas. He wrote a manifesto for the movement, about which Eric recurrently remarks: “none of the rest of us signed”. Continuing, Eric explains that to begin with Maciunas completely misunderstood Fluxus, “he thought we were a neo-Dadaist movement. Dada was obsessed with the question, is this art? But for us this question was irrelevant, we never made any separation between art and other aspects of life.”

While it is obvious that Erik liked Maciunas: “He was something as wonderfully contradictory as a 100% Leninist and a 100% Anarchist at the same time, and he had a fantastic sense of humour...Maciunas was also one of the best graphic artist I've ever known.”

Eric remarks that the terminology later used to describe internet was used by Fluxus as early as in the 60s to describe their global network, and that they were the only avant-gardists where a large proportion were female artists.

Like most of the artists involved in Fluxus Eric Andersen did not have a visual arts background. He was educated a composer. His first publicly performed piece was at the Thorvaldsen's Museum in Copenhagen 1959. A composition that was unplayable as it contained contradicting instructions and a complexity so large that even if the musicians had years to practice playing the piece it would be impossible to play it without mistakes.

The Kunsthal Nikolaj in Copenhagen, previously called Nikolaj Church was also the venue where Eric Andersen's artistic career took off for real. This when he nineteen years old participating in one of the first Fluxus arrangements. Exhibitions that today are recognised as legendary and probably one of the few instances where Scandinavians put their profound mark on the international art scene. The writings about the Fluxus movement can fill meter upon meter of shelf space, however, the more you read the more confused you get. On the contrary, Eric's version is simple and comprehensible, “It was never an -ism, it was simply a network of artists with the one thing in common that we were involved in Intermedia Art early on (...) The Network meant having somewhere to stay when putting on an event somewhere in the world, and it made collaborations available.” Then Eric points out that he himself, as with most other Fluxus artists, has done more work outside of the Network than within.

The Fluxus movement's self-appointed leader was George Maciunas. He wrote a manifesto for the movement, about which Eric recurrently remarks: “none of the rest of us signed”. Continuing, Eric explains that to begin with Maciunas completely misunderstood Fluxus, “he thought we were a neo-Dadaist movement. Dada was obsessed with the question, is this art? But for us this question was irrelevant, we never made any separation between art and other aspects of life.”

While it is obvious that Erik liked Maciunas: “He was something as wonderfully contradictory as a 100% Leninist and a 100% Anarchist at the same time, and he had a fantastic sense of humour...Maciunas was also one of the best graphic artist I've ever known.”

Eric remarks that the terminology later used to describe internet was used by Fluxus as early as in the 60s to describe their global network, and that they were the only avant-gardists where a large proportion were female artists.

Like most of the artists involved in Fluxus Eric Andersen did not have a visual arts background. He was educated a composer. His first publicly performed piece was at the Thorvaldsen's Museum in Copenhagen 1959. A composition that was unplayable as it contained contradicting instructions and a complexity so large that even if the musicians had years to practice playing the piece it would be impossible to play it without mistakes.

The letter from Moscow

When I meet Eric Andersen for the fist time he starts off warning me about a fake Fluxus artist, a person who claims to belong to the movement but never did. This sounds like a proper Fluxus myth, in the same spirit as when Eric Andersen fabricated several untrue stories about himself. Neither can I guarantee that he didn't serve me some made up stories. The most famous lie he created was served in the form of a letter addressed to George Maciunas in New York sent from Moscow. A lie Andersen willingly admits was indeed a lie. In 1964, midst the days of the Cold War, Eric and his brother Tony Andersen were travelling for three months through Eastern Europe.

In Poland, the most open of the Eastern countries, they started developing their network within the Eastern avant-garde. Contacts which led to meeting many of the avant-garde artists on that side of the Iron Curtain (when the situation hardened after 1968, the Polish were the only ones he could continue to contact). Their journey continued from Poland to Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the Soviet Union.

"At that time the Soviet Union thought of Denmark as a darling, the most Nato sceptical country of all the Nato countries... all other tourists would have to register at a police station when they arrived somewhere in Soviet, but we were Danish and we were 'comrades' so we were allowed to travel around in our car as we pleased.”

When arriving in Moscow Eric wanted to please George Maciunas with a small letter announcing that Fluxus had entered that city. This was something that Maciunas had painted great plans for when the two of them met in Copenhagen a few years earlier. Eric explains: “I wrote that Fluxus now had arrived to Moscow and that we performed a huge concert at The Red Square with thousands attending the audience. Amongst others we did Maciunas' performance Pissing Contest, (who can urinate furthest), and Nam June Paik's Penis Symphony”. The letter was signed with Eric's name, Arthur Köpcke, Emmett Williams and Tomas Schmit, the three others all well known Fluxus artists. Of course, none of the others were in Moscow and the whole story was a lie, but he knew them well enough to know that they would appreciate his joke, and he could easily imitate their signatures. Eric continues: “I thought that Maciunas would be happy, but instead he was furious about us stealing his project. He immediately wrote a letter to the Soviet Union General Secretary Nikita Chrusjtjov completely disassociating himself to what we – the four idiots had done.

He excluded us from Fluxus and asked Chrusjtjov to imprison us immediately.” However George Maciunas' mood soon changed, half a year later Eric was invited to the Fluxus Festival in New York and he lived in Maciunas' apartment for a few weeks. To add to the story, Nikita Chrusjtjov fell from power the same day that Eric claimed they'd put up the performance.

When I meet Eric Andersen for the fist time he starts off warning me about a fake Fluxus artist, a person who claims to belong to the movement but never did. This sounds like a proper Fluxus myth, in the same spirit as when Eric Andersen fabricated several untrue stories about himself. Neither can I guarantee that he didn't serve me some made up stories. The most famous lie he created was served in the form of a letter addressed to George Maciunas in New York sent from Moscow. A lie Andersen willingly admits was indeed a lie. In 1964, midst the days of the Cold War, Eric and his brother Tony Andersen were travelling for three months through Eastern Europe.

In Poland, the most open of the Eastern countries, they started developing their network within the Eastern avant-garde. Contacts which led to meeting many of the avant-garde artists on that side of the Iron Curtain (when the situation hardened after 1968, the Polish were the only ones he could continue to contact). Their journey continued from Poland to Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the Soviet Union.

"At that time the Soviet Union thought of Denmark as a darling, the most Nato sceptical country of all the Nato countries... all other tourists would have to register at a police station when they arrived somewhere in Soviet, but we were Danish and we were 'comrades' so we were allowed to travel around in our car as we pleased.”

When arriving in Moscow Eric wanted to please George Maciunas with a small letter announcing that Fluxus had entered that city. This was something that Maciunas had painted great plans for when the two of them met in Copenhagen a few years earlier. Eric explains: “I wrote that Fluxus now had arrived to Moscow and that we performed a huge concert at The Red Square with thousands attending the audience. Amongst others we did Maciunas' performance Pissing Contest, (who can urinate furthest), and Nam June Paik's Penis Symphony”. The letter was signed with Eric's name, Arthur Köpcke, Emmett Williams and Tomas Schmit, the three others all well known Fluxus artists. Of course, none of the others were in Moscow and the whole story was a lie, but he knew them well enough to know that they would appreciate his joke, and he could easily imitate their signatures. Eric continues: “I thought that Maciunas would be happy, but instead he was furious about us stealing his project. He immediately wrote a letter to the Soviet Union General Secretary Nikita Chrusjtjov completely disassociating himself to what we – the four idiots had done.

He excluded us from Fluxus and asked Chrusjtjov to imprison us immediately.” However George Maciunas' mood soon changed, half a year later Eric was invited to the Fluxus Festival in New York and he lived in Maciunas' apartment for a few weeks. To add to the story, Nikita Chrusjtjov fell from power the same day that Eric claimed they'd put up the performance.

From the preservation of the Monarchy to the Idle of the Year

It began in 1982 with a suggestion aimed to secure the existence of monarchy in Denmark for all eternity. A proposal that Eric Andersen sent to both the Queen and the Danish Government. The idea was that upon her death her two sons would inherit half of the kingdom each. Then their children again would similarly continue to inherit equal parts of the kingdom. “The splitting would continue like this until everyone in Denmark had their own kingdom.” The proposal never prompted any response from the respondents.

Unsuccessful with his proposal Eric thought that he should do something different to honour the Royal institution. The result was Homage to Emma Gad August 29 th 1982, a piece which later led tofounding the Idle of the Year.

Emma Gad, born January 21 st 1852, is in Denmark first and foremost known for her book on etiquette Etiquette - About Dealing with People from 1918. However, Gad's book did not aim to establish a standard for how to behave, but rather equip rural girls with etiquette to preserve their respect and dignity when working for the bourgeoisie in the cities.

Eric wrote an application asking to arrange a demonstration at the Amalienborg Square in the middle of the Royal Palace, on August 29 th 1982, to celebrate the “165 th anniversary of Emma Gad's birth”. August 29 th is also an important date in Danish history, as at the same date in 1943, the Danish Government resigned to the Nazi occupation, which led to German military arresting most of the country's police force.

Thus there were several reasons to create an event on the 29 th. of August at Amalienborg Square. Advocate for the preservation of the Monarchy through partitioning, and to celebrate both the Danish Police and Emma Gad.

He invited 165 women to the event. The women was selected so that everyone knew at least five other of the invitees, but no-one knew more than ten. All but 26 of them could bring one companion. All the invitees could veto against four other participants, two invited and two companions. The attendees could choose between 34 different dishes, 40 drinks, 25 different forms of entertainment such as a parrot show, a striptease, a brass band. 13 different ways of transport to the event, ranging from submarine to helicopter to bicycle; at their own expense. They where also offered 15 different newspapers to read. 63 of the invitees accepted to participate. At the same time 86 had placed veto against others attending. The final number of participants was minus 23 people. Minus 23 people attending a demonstration where 165 have been invited is rather unlikely. So unlikely that the chance of a nuclear plant to suffer a meltdown is twice as large, according to Niels Bak, one of the greatest Danish mathematicians of the time. As it is commonly known that a nuclear plant suffering a meltdown is nearly impossible, still the chance for it to happen is double the chance of what happened at Amalienborg thus this can't be viewed as anything less than a miracle.

There were already three good reasons to make August 29 th a red-letter day and now even a miracle had occurred at the Palace on this date, Eric felt that it was worth writing to the Queen Margrethe and the Government about this matter. Also this time he received ignorant silence. This is why he decided to make the day a red-letter date for himself. A day he named Idle of the Year.

The year after Idle of the Year was celebrated by Eric hiring a radio reporter to ask people in Copenhagen on their views on attending the celebration of Idle of the Year; all of them said they found it fantastic! No-one asked what it was all about.

In 1984 Idle of the Year became a collaboration with the Ethnological Museum in Copenhagen. He made an exhibition at the museum and the institution got the Idle of the Year registered as an ethnographic observation. The exhibition described the background of the project, but mainly encouraged visitors to partake in his Idle of the Year event for this year, The Idle walk of the Year.

At The Idle walk of the Year, the 29 th August 1984 he invited the Anarchistic drama group Berserk, and instructed them to carry a variety of objects from the museum to Amalienborg Square while walking as slowly as possible without standing still. As a result all traffic in central Copenhagen came to a stand still for six hours. Eric describes:

“The police was completely in on it. You could see a motorcycle police officer wearing a Year of the Idle badge on his chest pocket while driving his bike as slowly as he could through the city. Nothing at all happened that required their attention throughout those hours, so of course they were happy.”

Eric himself polished the Palace Square using Petroleum, like the Ethnological Museum had done to their wooden floors since the nineteenth century. A tradition Eric found so fascinating that hebrought it to the Palace Square.

Since 1986 the Idle of the Year has never been advertised in advance of the event, but it still continues to exist.

It began in 1982 with a suggestion aimed to secure the existence of monarchy in Denmark for all eternity. A proposal that Eric Andersen sent to both the Queen and the Danish Government. The idea was that upon her death her two sons would inherit half of the kingdom each. Then their children again would similarly continue to inherit equal parts of the kingdom. “The splitting would continue like this until everyone in Denmark had their own kingdom.” The proposal never prompted any response from the respondents.

Unsuccessful with his proposal Eric thought that he should do something different to honour the Royal institution. The result was Homage to Emma Gad August 29 th 1982, a piece which later led tofounding the Idle of the Year.

Emma Gad, born January 21 st 1852, is in Denmark first and foremost known for her book on etiquette Etiquette - About Dealing with People from 1918. However, Gad's book did not aim to establish a standard for how to behave, but rather equip rural girls with etiquette to preserve their respect and dignity when working for the bourgeoisie in the cities.

Eric wrote an application asking to arrange a demonstration at the Amalienborg Square in the middle of the Royal Palace, on August 29 th 1982, to celebrate the “165 th anniversary of Emma Gad's birth”. August 29 th is also an important date in Danish history, as at the same date in 1943, the Danish Government resigned to the Nazi occupation, which led to German military arresting most of the country's police force.

Thus there were several reasons to create an event on the 29 th. of August at Amalienborg Square. Advocate for the preservation of the Monarchy through partitioning, and to celebrate both the Danish Police and Emma Gad.

He invited 165 women to the event. The women was selected so that everyone knew at least five other of the invitees, but no-one knew more than ten. All but 26 of them could bring one companion. All the invitees could veto against four other participants, two invited and two companions. The attendees could choose between 34 different dishes, 40 drinks, 25 different forms of entertainment such as a parrot show, a striptease, a brass band. 13 different ways of transport to the event, ranging from submarine to helicopter to bicycle; at their own expense. They where also offered 15 different newspapers to read. 63 of the invitees accepted to participate. At the same time 86 had placed veto against others attending. The final number of participants was minus 23 people. Minus 23 people attending a demonstration where 165 have been invited is rather unlikely. So unlikely that the chance of a nuclear plant to suffer a meltdown is twice as large, according to Niels Bak, one of the greatest Danish mathematicians of the time. As it is commonly known that a nuclear plant suffering a meltdown is nearly impossible, still the chance for it to happen is double the chance of what happened at Amalienborg thus this can't be viewed as anything less than a miracle.

There were already three good reasons to make August 29 th a red-letter day and now even a miracle had occurred at the Palace on this date, Eric felt that it was worth writing to the Queen Margrethe and the Government about this matter. Also this time he received ignorant silence. This is why he decided to make the day a red-letter date for himself. A day he named Idle of the Year.

The year after Idle of the Year was celebrated by Eric hiring a radio reporter to ask people in Copenhagen on their views on attending the celebration of Idle of the Year; all of them said they found it fantastic! No-one asked what it was all about.

In 1984 Idle of the Year became a collaboration with the Ethnological Museum in Copenhagen. He made an exhibition at the museum and the institution got the Idle of the Year registered as an ethnographic observation. The exhibition described the background of the project, but mainly encouraged visitors to partake in his Idle of the Year event for this year, The Idle walk of the Year.

At The Idle walk of the Year, the 29 th August 1984 he invited the Anarchistic drama group Berserk, and instructed them to carry a variety of objects from the museum to Amalienborg Square while walking as slowly as possible without standing still. As a result all traffic in central Copenhagen came to a stand still for six hours. Eric describes:

“The police was completely in on it. You could see a motorcycle police officer wearing a Year of the Idle badge on his chest pocket while driving his bike as slowly as he could through the city. Nothing at all happened that required their attention throughout those hours, so of course they were happy.”

Eric himself polished the Palace Square using Petroleum, like the Ethnological Museum had done to their wooden floors since the nineteenth century. A tradition Eric found so fascinating that hebrought it to the Palace Square.

Since 1986 the Idle of the Year has never been advertised in advance of the event, but it still continues to exist.

Mitologia della Lingua

Many of Andersen's works have come to existence through collaborations with Italian collectors. Collaborations that also led to Andersen living in Italy for years. These Italian art collectors did not solely focus on buying objects like most collectors today, but did instead adopt the classic role of patrons. They wanted the artists to come and live with them so they could gain knowledge and be present at the artistic process. The collector who Eric first and foremost collaborated with in Italy is Carlo Cattelani. A man who lived a profane life in the meat industry. Carlo started to collect pop art, a collection he then sold on to begin collecting Fluxus and religious contemporary art instead.

When Andersen was asked to contribute to this collection it resulted in a piece containing the basic elements of the Catholic Mass' liturgical order: the procession, the meaning of the word / the Sermon, and the communion.

Like many of Anderson's works this is a fusion of event and object. As an object it consists of a confessional furnished with a kitchen, a cookbook, menus and two tables with parasols and four chairs. The cookbook, named Cucina confessionalale, confession of the kitchen, contains the recipe to nine traditional Italian dishes made of tongue. The entire work's title alludes as much to the tongue as to the word, as Mitologia della Lingus can be translated into both the word's or the tongue's mythology. The menus are embroidered with gold lettering on a mesh fabric normally used for lingerie and therefore has an erotic effect.

When Eric and Carlo approached the Vatican with their wish to be granted a confessional from which to build the piece they were met with suspicion. Church inventory is regarded sacred material and to wrongly acquire such could give fifteen years incarceration, thus the special authorisations for transportation. After a prolonged argument with the Vatican they finally got a confessional from the 1730s.

The piece was exhibited for the first time in a small Tuscany town where the local priest was known as a superb chef. This priest was the one preparing tongue dishes in the confessional, while the town residents sat by the tables eating.

Eric concludes that a work of art like this would have been impossible to accomplish without the collaboration with a collector like Carlo Cattelani.

The never ending book and the relocation of London

The assertion that proper art asks more questions than gives answers is an undeniable cliché. Eric has taken this a step further, as he in several pieces has worked on making it so that the more you take part in them the more confused you get. Several of the films he screened in Liaison arestructured this way, and several of the texts he has written are also constructed in this manner.

Even though Eric generally oppose exhibition catalogues he created one in relation to his exhibition at the Ethnological Museum in Copenhagen. A tiny book that in many ways captures Andersen's philosophy in it's entirety. Nor is it reminiscent of any traditional exhibition catalogue. The book is gold coloured, but other than that it doesn't look particularly out of the ordinary. A small booklet 10 x 7 cm large, consisting of approximately 30 pages. When reading it you soon realise that this book will leave you puzzled. Eric did not write the book himself, but had four ethnologists find the texts in anthropological works. The main text is easily read: 'The journey is strenuous but necessary”. Then there are all the foot notes. One footnote subsequently results in one or several footnotes, which results in a never ending reading of the footnotes - so the book offers a never-ending studies in humanity.

The book's gold colour is due to the metal's specific role in the anthropology. Personally he views the book as a “tour and procession” through the humanity. And that is exactly what a large part of his body of work is all about, to create rites, rites that create a fascination with life itself. Within this is also the interaction between art, life and science.

The fact that I, when writing this article believe I'm sitting in an apartment on Telegraph Hill in South East London depends on the organisational level of reality I happen to be in. Actually, in reality I might be in German Bad Salzdetfurth, because Eric Anderson happened to relocate the entire London from England to Germany 44 years ago.

The reason why Andersen moved London to the small community of Bad Salzdetfurt is far easier to understand than how the actual relocation proceeded. It was simply because he concluded that London was at the end of its existence. The city which emerged about 2000 years ago will in another 1500 years mainly lie below the sea level. This because the island is rising in the Northwest and sinking in the South where London is located.

Proving that the relocation of London actually took place is impossible, because it took place at a level beyond our preference archive, at a biochemical level. A level that controls our consciousness and instincts and therefore also the geographical structures and the history of the nations.

Art / Politics / Society

One of Andersen's early works consists of a classic vending machine – one of those where the goods are contained in small boxes. In each of the boxes there are four Danish Kroner and to open a box you have to insert four Danish Kroner. The piece is totally transparent. You know exactly what you will get and what you have to pay for it.

At the end of our conversation Eric points to my notes with the final subject I want to ask him about, the relation between Art/Politics/Society. “Haven't we not talked about this the whole time?”

In the notes about this subjects I had wrote a quote by Andersen: “I don't think it's important for the art world, I think it's important for the rest of the world that art is a part of the universe.

Politics and art is very different. In politics you argue for solutions, for specific solutions, for specific problems that you can find. Your don't do that in art. In art you rise questions and you propose alternative existence, perception and understanding. So it's quite two different things and I think politics should be a little more like art.”

But even though he considers the topic as thoroughly clarified, he then proceeds to develop hisargument:

'I understand art and culture as contradictions. Culture is the way we understand nature. Without culture we are unable to perceive our surroundings. Culture requires unity, revisionism and security. Where as art rebels against the stereotypes and the hypocrisy culture is always reflecting. What culture does is to invent a cultural art, an art that will serve as a instrument for the ruling power. The artists on the other hand, pretend to create cultural art, but in the piece itself they do something completely different, something that culture is unable to comprehend, still constantly being a bit amusing to culture... If you just hang in there long enough culture is in the end so fragile that it will give in. In my youth I knew the painter and sculptor, Gunnar Aagaard Andersen. He was a bit controversial at the time, but not more controversial than that he could later become a professor. He said that if you just hang in there long enough culture is so weak that after twenty years or so you will have shaken the world so much that it gives in and feeds you.'

And so with this Eric concludes that the other Andersen was right. For Eric, it did take twenty working years before he was able to make a living through his art, before then, he worked as a truck driver, as Head of Unit within public care services, and for a while he was an expert on bankruptcies.

Many of Andersen's works have come to existence through collaborations with Italian collectors. Collaborations that also led to Andersen living in Italy for years. These Italian art collectors did not solely focus on buying objects like most collectors today, but did instead adopt the classic role of patrons. They wanted the artists to come and live with them so they could gain knowledge and be present at the artistic process. The collector who Eric first and foremost collaborated with in Italy is Carlo Cattelani. A man who lived a profane life in the meat industry. Carlo started to collect pop art, a collection he then sold on to begin collecting Fluxus and religious contemporary art instead.

When Andersen was asked to contribute to this collection it resulted in a piece containing the basic elements of the Catholic Mass' liturgical order: the procession, the meaning of the word / the Sermon, and the communion.

Like many of Anderson's works this is a fusion of event and object. As an object it consists of a confessional furnished with a kitchen, a cookbook, menus and two tables with parasols and four chairs. The cookbook, named Cucina confessionalale, confession of the kitchen, contains the recipe to nine traditional Italian dishes made of tongue. The entire work's title alludes as much to the tongue as to the word, as Mitologia della Lingus can be translated into both the word's or the tongue's mythology. The menus are embroidered with gold lettering on a mesh fabric normally used for lingerie and therefore has an erotic effect.

When Eric and Carlo approached the Vatican with their wish to be granted a confessional from which to build the piece they were met with suspicion. Church inventory is regarded sacred material and to wrongly acquire such could give fifteen years incarceration, thus the special authorisations for transportation. After a prolonged argument with the Vatican they finally got a confessional from the 1730s.

The piece was exhibited for the first time in a small Tuscany town where the local priest was known as a superb chef. This priest was the one preparing tongue dishes in the confessional, while the town residents sat by the tables eating.

Eric concludes that a work of art like this would have been impossible to accomplish without the collaboration with a collector like Carlo Cattelani.

The never ending book and the relocation of London

The assertion that proper art asks more questions than gives answers is an undeniable cliché. Eric has taken this a step further, as he in several pieces has worked on making it so that the more you take part in them the more confused you get. Several of the films he screened in Liaison arestructured this way, and several of the texts he has written are also constructed in this manner.

Even though Eric generally oppose exhibition catalogues he created one in relation to his exhibition at the Ethnological Museum in Copenhagen. A tiny book that in many ways captures Andersen's philosophy in it's entirety. Nor is it reminiscent of any traditional exhibition catalogue. The book is gold coloured, but other than that it doesn't look particularly out of the ordinary. A small booklet 10 x 7 cm large, consisting of approximately 30 pages. When reading it you soon realise that this book will leave you puzzled. Eric did not write the book himself, but had four ethnologists find the texts in anthropological works. The main text is easily read: 'The journey is strenuous but necessary”. Then there are all the foot notes. One footnote subsequently results in one or several footnotes, which results in a never ending reading of the footnotes - so the book offers a never-ending studies in humanity.

The book's gold colour is due to the metal's specific role in the anthropology. Personally he views the book as a “tour and procession” through the humanity. And that is exactly what a large part of his body of work is all about, to create rites, rites that create a fascination with life itself. Within this is also the interaction between art, life and science.

The fact that I, when writing this article believe I'm sitting in an apartment on Telegraph Hill in South East London depends on the organisational level of reality I happen to be in. Actually, in reality I might be in German Bad Salzdetfurth, because Eric Anderson happened to relocate the entire London from England to Germany 44 years ago.

The reason why Andersen moved London to the small community of Bad Salzdetfurt is far easier to understand than how the actual relocation proceeded. It was simply because he concluded that London was at the end of its existence. The city which emerged about 2000 years ago will in another 1500 years mainly lie below the sea level. This because the island is rising in the Northwest and sinking in the South where London is located.

Proving that the relocation of London actually took place is impossible, because it took place at a level beyond our preference archive, at a biochemical level. A level that controls our consciousness and instincts and therefore also the geographical structures and the history of the nations.

Art / Politics / Society

One of Andersen's early works consists of a classic vending machine – one of those where the goods are contained in small boxes. In each of the boxes there are four Danish Kroner and to open a box you have to insert four Danish Kroner. The piece is totally transparent. You know exactly what you will get and what you have to pay for it.

At the end of our conversation Eric points to my notes with the final subject I want to ask him about, the relation between Art/Politics/Society. “Haven't we not talked about this the whole time?”

In the notes about this subjects I had wrote a quote by Andersen: “I don't think it's important for the art world, I think it's important for the rest of the world that art is a part of the universe.

Politics and art is very different. In politics you argue for solutions, for specific solutions, for specific problems that you can find. Your don't do that in art. In art you rise questions and you propose alternative existence, perception and understanding. So it's quite two different things and I think politics should be a little more like art.”

But even though he considers the topic as thoroughly clarified, he then proceeds to develop hisargument:

'I understand art and culture as contradictions. Culture is the way we understand nature. Without culture we are unable to perceive our surroundings. Culture requires unity, revisionism and security. Where as art rebels against the stereotypes and the hypocrisy culture is always reflecting. What culture does is to invent a cultural art, an art that will serve as a instrument for the ruling power. The artists on the other hand, pretend to create cultural art, but in the piece itself they do something completely different, something that culture is unable to comprehend, still constantly being a bit amusing to culture... If you just hang in there long enough culture is in the end so fragile that it will give in. In my youth I knew the painter and sculptor, Gunnar Aagaard Andersen. He was a bit controversial at the time, but not more controversial than that he could later become a professor. He said that if you just hang in there long enough culture is so weak that after twenty years or so you will have shaken the world so much that it gives in and feeds you.'

And so with this Eric concludes that the other Andersen was right. For Eric, it did take twenty working years before he was able to make a living through his art, before then, he worked as a truck driver, as Head of Unit within public care services, and for a while he was an expert on bankruptcies.